Yesterday afternoon the Urban Studies Program had the honor of hosting University of Southern California professor, Manuel Pastor Jr. as the 2011 Urban Studies Model Scholar. His visit marked the sixth annual Model Scholar event—a tradition in the Program that, along with an afternoon lecture, includes an opportunity for the senior Urban Studies majors (who collaboratively choose and invited the scholar during their junior year) to have lunch with the visiting scholar. If I were a senior I would give myself a pat on the back—Professor Pastor’s lecture was eye opening, inspirational, witty, and undoubtedly a display of scholarship worth emulating.

Pastor is a professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at USC, the Director of USC’s Program for Environmental and Regional Equity and the Co-Director of USC’s Center for Immigrant Integration. The title of his lecture? “Change is Gonna Come” Why? Changing demographics.

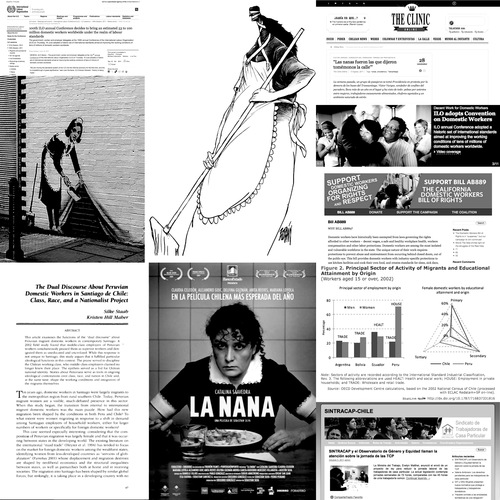

Inequality, shortsighted policy, and social chasms are themes with which most urban studies majors are all too familiar—they pop up in our readings, our discussions, and our exams, and they may define many of our future jobs. Pastor used these same classic themes to describe the changing urban (and suburban) reality, and yet, the stories, facts and analyses he shared were startling and unexpected. For example, most people believe that immigration into southern California is the highest is had ever been. It turns out this is wrong; Los Angeles has not seen immigrantgrowth in the last three years. The Latino population in LA has grown by 43% since the last decade, but this is due to growth within the long-term immigrant population—the second and third generation immigrants. “LA is now a ‘home-grown’ city,” says Pastor.

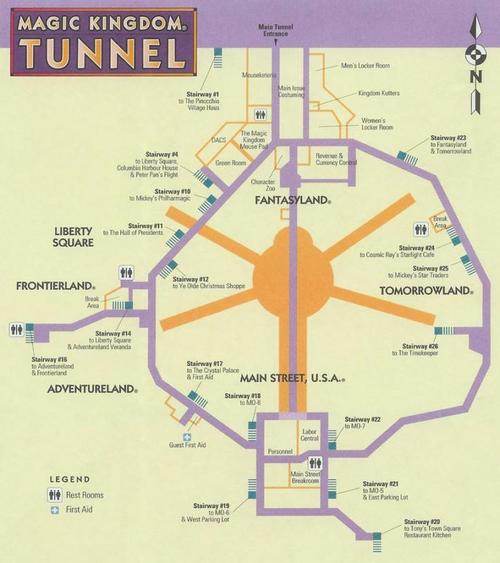

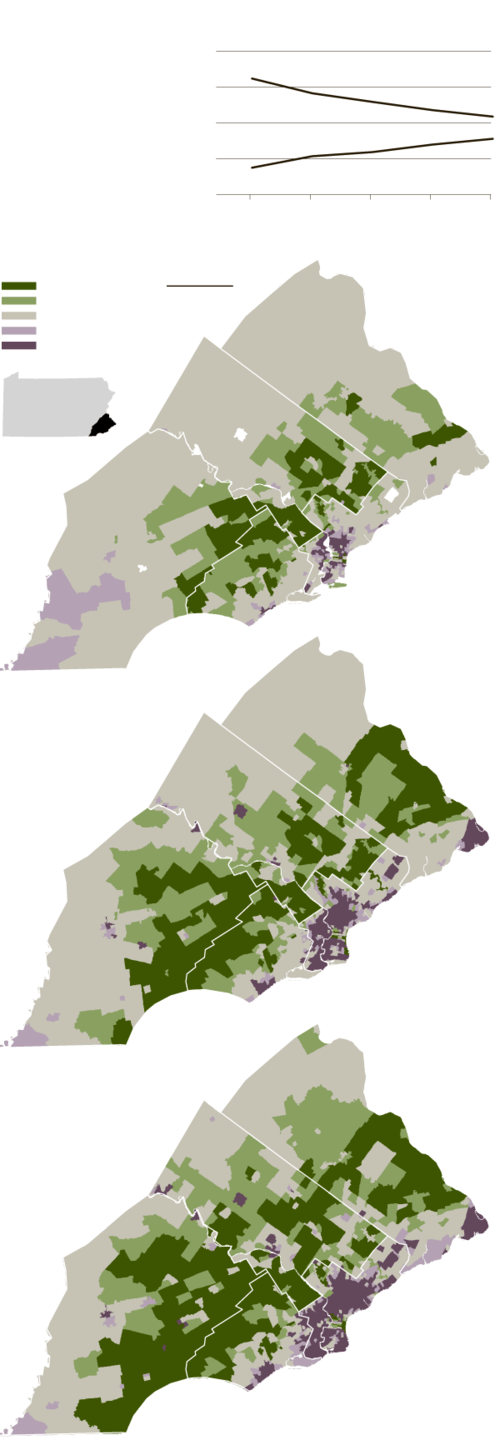

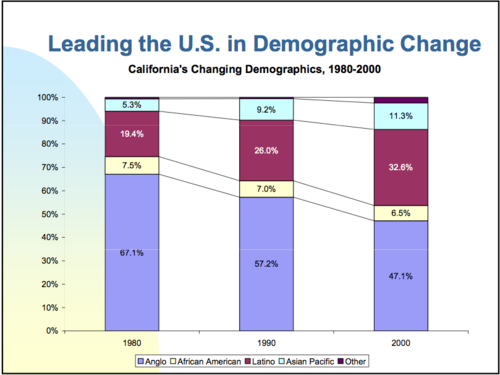

America is up in arms about the immigration problem in California when, in point of fact, we are seeing a decrease in immigration and a California that already worked through the worst of it’s immigration turmoil during the 80’s and 90’s. When Pastor says “change is gonna come” he is referring to a nation in which California is ahead of the curve. California is already a majority minority state, and has been since 1999. The nation isn’t far behind, however, with predictions to be majority minority by 2042. What’s more, this change is not isolated to the cities as most people assume. Based on 2010 Census data, the suburbs exactly mirror American demographics.

Source: Pastor’s Powerpoint

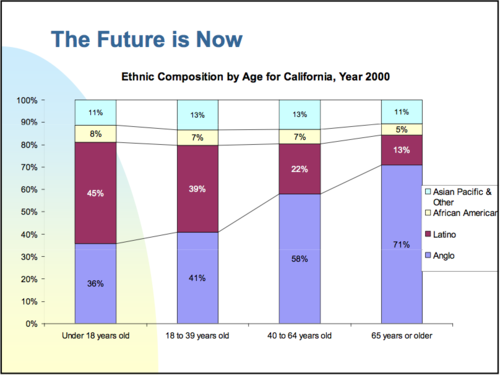

What are the impacts of these demographic shifts? For one, a demographic generation gap that is pitting the younger minority-dominated generations against an aging white population. The median age of whites in America is 41 years, while the median age of the Latino population is only 27 years. This trend is seen across the nation (the biggest gap is in Phoenix, AZ) and the effects of this disparity are profound. Research by Pastor, as well as more typically conservative groups like IMF, have found that communities with the largest gaps have the lowest spending on education. The older generations don’t see themselves in the younger generations and as a result don’t feel the need to support the younger generations financially or otherwise. On the flipside the older generations are increasingly dependent on government-subsidized programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, which require financial contributions from the younger generations.

Source: Pastor’s Powerpoint

“As a whole,” said Pastor, “the American population is unequal, deregulated, and disconnected”. In the end, these divisions are driving the lack of economic growth and spurring much of the motivation behind the Occupy Movement. We are the “99%” is a positive message in holistically divided nation. Change is coming and the first step is to OCCUPY!

Recent Comments